I realised with sadness the other day that I have never been able to bird properly. I have seen plenty of birds over the years that I have been birding, and have become very proficient in the identification of them. But have I really been able to see the bird for the feathers? When I started bird watching as a youngster I had the advantage of very keen eyesight and access to my father’s binoculars, which were good quality in the 80s. Looing through these same binoculars today, they are comparatively dull to even the entry level pairs that are available for purchase now. Thus with keen vision the optics did not allow me to “really” see the bird. With the passing years the optics have improved tremendously and I am now in possession of brilliant optics but sadly I can still not really see the bird as the years have not been kind on my eyesight.

Fortunately this can be remedied today with the brilliant ranges of spectacle lenses and contact lenses available on the market. Lucky are those of you who have been able to use contact lenses from the start. I have had to do with glasses for most of these years due to astigmatism. Toric contact lenses, although first developed in 2000, has only in the past few years really come into its own right allowing astigmatic people to change comfortably over to contact lenses. Due to this I still find myself birding to a large degree with my glasses on.

When I started off with permanently wearing glasses I battled with flicking the glasses up when using the binoculars, as in those days the most eye relief one could get was to flap the 5mm of the rubber eyepiece over backwards. This in no way improved what you could see through the binoculars. Manufactures are thankfully now producing binoculars with easy adjustable eye relief that provides enough relief to allow for comfortable bird watching with glasses. For someone that today bird with glasses and with contact lenses this is a huge improvement and makes for easy use in both cases. It is important that if you should do this, to ensure that the binoculars that you purchase have a decent locking mechanism that will not easily wear with the regular adjustment.

We now have a great pair of binoculars and a decent set of glasses and finally we can really see the bird. Not quite! It all depends on your frames. I have had quite a number of pairs of glasses over the years and have learned that some of them are brilliant for using with binoculars and some are just down right horrible or unusable.

When selecting your pair of glasses at the optometrist the first and foremost criteria is that the pair should fit comfortably and be so for long periods of time. All the standard measures of fit need to be taken into account and your optometrist will provide the best advice on this. This includes the fit over the bridge of your nose, the width of the glasses across your face, length of the arms and ensuring that it does not rest on your cheeks.

Secondly and almost just as important is how well the glasses suit your face shape and the look you want to achieve. As mentioned your optometrist will provide the best advice on this, and I am by no means qualified to do so.

As a birder there are however certain other aspects of the frame to consider to ensure that the use of your binoculars are as comfortable and optimum as possible. These requirements I have learned with different frames and in some I have made some horrible mistakes that I won’t repeat again. Of course adding these requirements to the above, and mentioning them to the optometrist makes finding the correct pair a little harder, but well worth the effort. The other option is to do what I now days do. I now have my normal day to day glasses and an additional pair that I call my birding glasses. These glasses conform to all my binocular requirements, and therefore I spend the additional cost of keeping their lenses updated as well.

What are these additional requirements that are needed in a birding pair of glasses? I had a discussion with a local optician and optometrist and discussed with them the key items and the effect on the glasses and the use of binoculars.

Firstly and the most importantly is the angle of the depth of the lens called pantoscopic tilt. This is the angle at which the lens is slanted from top to bottom. The easiest way to see this is to place the glasses on a flat surface with the arms open. Looking from the side you can see the slant to the lenses. All frames are slanted slightly, meaning that the top of the lens overhangs the bottom of the lens. This is primary to ensure that when looking forward and downward your eyes look properly through the lens for seeing far and reading or looking down. Although the degree if tilt is around 8-15 degrees the difference this makes can be significant. The higher it becomes, the larger the gap between the bottom of the eye piece of the binocular and the bottom of you glasses. This will decrease the field of vision in the binoculars and increase the amount of black rings you see. Placing the binoculars flush against the glasses, which one tends to try and do will result the binoculars to point uncomfortably downwards. Unfortunately the degree of slant on the lenses is not indicated on the frame, and thus you will need to look at the frames with the mock lenses from the side and establish which pair has the most upright position. Pantoscopic tilt is something that you should look at with your optician as not having enough tilt or tilt in the opposite direction (retroscopic tilt) could cause refractive errors.

Coupled closely with tilt is facial wrap. This is the amount that the frame wraps around the width of the face. Most modern frames have a slight wrapping. Coupled to the wrap is the amount of rounding in the lens itself to wrap around the side of the face. Facial wrap can go from none, to full wrap around, but very few glasses extends to the amount of wrap one gets in sunglasses especially cycling or skiing glasses. Some glasses have no wrap at all. The purpose of wrap is firstly to increase peripheral vision and secondly it helps minimise reflections in the lens from behind. Some wrap is thus needed, but be aware that excessive wrap will cause the same problem as panoscopic tilt, with a gap between the eye piece and the glass lens but now on the outer side of the binocular, causing the same reduction in field of vision and increase in black areas.

The standard guideline for lens depth, the top to bottom measurement of the lens is described as 7mm from the centre of the pupil upward and 14mm downward as the minimum, a total of 21mm. Correct lens depth ensures that the top and bottom of the frame fades into your peripheral vision making the glasses mostly unnoticed when wearing it. With the improvement of thin frame and frameless glasses this becomes less noticeable and frame depth has decreased on some frames to less than this. Taking into account that the average binocular eye piece has a diameter of around 25mm aligning your glasses lens depth ensures for better comfort. With thick framed glasses the lens depth should be measured from the inner edges of the frame to ensure that the eye piece do not get raised too far off the lens by the frame it self. The best is to look through your binoculars when selecting the frame and check that the eye-piece seats nicely on the lens in the position that you will wear the glasses.

Some people have found that although they have two similar script glasses their vision is better with one pair than the other. The most common cause for this is vertex distance, which is the distance from the apex of the cornea to the lens, or simply put the gap between the eyeball and lens. Test this by moving your glasses slightly forward and backwards, and you will see that the focus alters slightly. The lens is crafted to have an optimal vertex distance, usually between 8-14mm. The difference in the clarity of the two pairs of glasses can then be due to one pair’s seating on the nose bridge being closer to the eye than the other pair. The general rule is that the glasses should sit on your face as close as possible to your eyes, but still conform to not touching either the cheeks or eyebrows. It should also not touch the eye lashes. This brings back the balance of pantoscopic tilt, as the right amount should align the lens slightly away from the eyebrow and lashes and closer to the cheeks to ensure the shortest vertex distance. If at all possible check with your optometrist if the vertex distance can be aligned as closely to the eye relief of your binoculars.

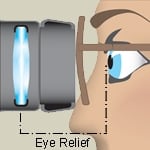

The eye relief of a pair of binoculars is how far back from the eyepiece your eye can be and still see the whole field of view without getting black out areas. If the distance to your eyes is greater than the binoculars eye relief, you will see only the centre section of the image.

In most cases an eye relief of 10 to 15mm is needed for the average eyeglass wearer to be comfortable. Ideally though you should look for binoculars and spotting scopes that have 16, 17 or even 18mm.

You might feel a bid odd taking you binoculars along to your next eye test and frame selection, but as most of us spend a lot of time and cost on the selection of our binoculars, better to spend time to ensure that you get the best out of them when birding with glasses. Most optometrist are very accommodating and understanding of these requirements, and once they know what you are looking for and why, will ensure that you get the best pair for not only looking good in, but birding good in.

Some further links

http://www.birdwatching.com/optics/binoculars6_eyerelief.html

http://fatbirder.com/links/fun/hints_and_tips.html

http://www.bestbinocularsreviews.com/blog/long-eye-relief-binoculars-for-bird-watching-06/